Robert Campbell junior was the owner and runholder of Run 300B, known as the Burwood Station. It was one of many high country South Island blocks created by the government in the 1850s and either sold off or long-term leased.

An ex-whaler, George Printz, on 21 November 1859, became the first leasehold owner of Burwood. The annual lease was £11.10s ($NZ23). Printz was born in Sydney, Australia, and he probably named Burwood after the Burwood Farm in West Sydney, which itself was named after Burwood Park in England. As originally defined, the Burwood run was bounded on the north by the Mavora run, on the east by the Oreti River, on the west by the Mararoa River, and on the south by the old Otago-Southland provincial boundary. The area was 35,900 acres (14,500 hectares).

The Burwood run was acquired from Printz by John McGregor and Thomas Constable Low in June 1867. Three years later, in August 1870, the Burwood block (300B) lease was purchased by Robert Campbell senior and son Robert, from the University of Otago, which had acquired this block and others as an endowment. At the same time, the Campbells acquired the Mavora block (Run 389) to the north of Burwood. The Campbells also leased the Takitimu block (Run 415) to the west of the Mavora block, and a year prior to this they had leased the Upper Eglington block (Run 416) of 74,000 acres. The land acquisition did not end there. By 1871 the Campbells had acquired Runs 391 (West Eyre) and the adjacent Run 190 (Five Rivers).

The pioneer runholders of the 1850s and1860s acquired their land from the government at very favourable terms. However, they faced massive challenges. Most of the runs were in the higher back country, with very little road access. Runholders were required to stock their farms within six months and they did so by driving mostly imported sheep up from the southern coast.

Besides providing shelter for themselves, one of the first challenges was to clear sufficient land for good pasturage for their flocks. Land not covered by bush was of generally poor foraging quality, consisting of tussock, flax, matagouri and other hardy plants. Burning was the easiest, quickest and cheapest way to clear the land of both bush and native pasture, but often burning was overdone, denuding the cover and leaving it prone to erosion and slippage. A trip through the high country districts reveals bare, eroded hillsides that would have been better in native bush and original growth. This problem was not created solely by the pioneer settlers. Fires were generated accidentally or deliberately by Maoris transiting the high country area searching for greenstone and native animals. Land surveyors also started fires to signal to one another in mapping the land, and to clear a path for themselves.

Some of the controlled burnings got out of hand causing widespread damage, loss of buildings, and destruction of wild life and habitats in northern Southland. Continued burning practices lowered soil fertility.

The high country forests were covered with mostly black, white and red birch, with red birch predominating. The cleared timber was used locally for building houses, woolsheds and barns, some was used for fencing and railings, and some marketed and sold commercially by sawmills. Most cleared timber was burned for heating purposes or just burned where it fell for land clearance.

Where it could be, land was ploughed and sowed with English grasses. Fencing led to better stock control and health. Red birch post and railings were used in the early fences. Wire fences started to become common in the 1860s and 1870s in the South Island sheep runs. They consisted of five plain wires with iron standards nine feet (2.7 metres) apart, and with 10 strainer posts to each mile (1.6 kilometres). Barbed wire appeared from the 1880s onwards.

In those early days, communication, or the lack of it, provided real difficulties for the pioneers. There were few roads, not much more than bullock tracks, and they were almost impassable in the winter months. Crossing rivers was a hazard, and one of the most common causes of accident. Local county councils put some effort into metaling roads, building culverts and spanning creeks and rivers.

In the early pioneering days, seed was scattered by hand and harvested by hand sickle or scything, then the grain or seed was thrashed by traditional hand methods. The first reaping machines were introduced to New Zealand in the 1860s followed by the reaper and binder machine in the late 1870s. Coal-fired traction machines became common by the 1890s and did much of the heavy-duty carting of wool bales and timber, and they provided power for wool sheds and sawmilling. Up until this stage farmers literally relied on horse power and water power.

The Campbells were bold and innovative business men and prepared to build extensively in a new and risky environment. The New Zealand sheep returns for 1871 showed that Robert Campbell, in partnership with W. Low, owned 140,000 sheep, while the younger Campbell, on five runs, ran 169,000 sheep in his own name and another 25,000 with a partner. This is an amazingly large holding, one of the biggest in the South Island of New Zealand. Burwood was only a small part of the Robert Campbell holdings.

By 1882 Robert Campbell and son, now incorporated as a London-based business, owned or leased 609,000 acres. From 1883 and 1884 they were running 290,000 sheep on their total leasehold and freehold lands.

Here are a few examples of his innovative contribution to New Zealand agriculture which impacted on his Burwood high country farming methods.

In February 1882 the first frozen meet shipment left Port Chalmers for London on the sailing ship Dunedin. Robert Campbell was one of the principals in arranging this first shipment. He chaired a meeting in February 1881 that led to the formation of a frozen sheep exporting company that resulted in New Zealand’s first export of frozen meet. Robert Campbell not only supplied sheep for this first shipment and many others, he was also a founding director of the New Zealand Refrigeration Company and a director of the New Zealand and Australian Land Company that arranged the shipments and the sale, at London’s Smithfield market, of the 5,000 mutton and lamb carcasses from these shipments.

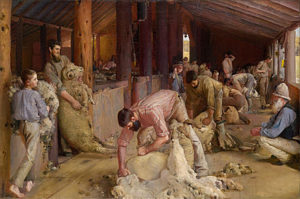

A second example is the introduction of mechanised shearing to New Zealand. An Australian inventor, Frederick Wolseley, came to New Zealand in early 1888 to demonstrate the first machine to shear sheep. Up to this stage shearing was done by hand clippers/shears. Robert Campbell sponsored the demonstration at his home Otekaike Station in north Otago, at which 100 people attended. Campbell was so impressed himself he ordered a machine for each of his stations.

A third example is Robert Campbell’s proactive efforts to control the rapid expansion of rabbits northwards from the mid-1870s onwards. This initiative led to James Selwood coming to New Zealand as a rabbiter who was assigned to Campbell’s Burwood Station. We examine the rabbit problem in the next section.

The new settlers were skilled at adapting imported farming equipment to suit local conditions. For instance, imported ploughs were inefficient in New Zealand’s marshy and tussock areas and settlers developed the swamp plough from 1890s.

Until frozen meat exports developed in the 1880s, wool was the only part of the sheep that was of any value. With decreasing wool prices, most stations, like Burwood, had a carcass rendering plant for boiling down and producing tallow to dispose of surplus stock. There was some export trade in canning works that exported tinned sheep and beef to Britain, but this industry was never large enough to deal with more than a fraction of the sheep and cattle available.

Until the advent of refrigerated shipping in the 1880s, the main pastoral exports were wool, skins and hides, leather and pelts, tallow, potted salted meat and livestock. The introduction of the frozen meat trade changed the whole scope of sheep farming. We had freezing works popping up around the country and within eight years, four freezing works opened in Southland, two at Bluff (in 1885 and 1892), and the others at Makarewa (1887) and Mataura (1893).

The frozen meat trade also changed sheep breeds in New Zealand. Until the 1880s the fine-wool merino was the breed of preference. Indeed, Robert Campbell was one of the leading breeders and regular award winners at Agricultural and Pastoral shows. Merinos had been bred for their wool, but by the early 1870s, pastoralists had no outlet for their surplus sheep except boiling them down for tallow (rendered fat, used for making soap and candles). The Merino was too lean to make this profitable, so, farmers looked to other breeds that would provide a better return. The profitability of frozen sheep shipments to the United Kingdom changed all this. What was needed was more muscled, meaty sheep for consumption. Cross-breeding and the importation of new breeds became the trend, leading to Merinos being marginalised to the semi-arid and mountainous country of the South Island. By 1900, 86 percent of the national flock was defined in government statistics as crossbreds and other long-wools.

Land was farmed more intensively, and farming practices were fine-tuned and improved. In the North Island settlers cleared more bush and sowed grasses and clovers. In the South Island tussock country was ploughed and turned into pasture. Turnips that had been sown for winter feed were used to fatten sheep, and larger areas were planted. In Southland, wetlands were drained, cultivated, and sown in pasture. Blood-and-bone, a by-product of the freezing works, and superphosphate became more widely used to fertilise pastures and feed crops.

New Zealand’s growth in the 19th century, in terms of immigration, transport and communication, was boosted by the nation-building visionary Julius Vogel. He was New Zealand’s Colonial Treasurer in 1870 and soon became the New Zealand Premier. In the 1870’s decade, New Zealand’s population almost doubled. The colony’s European population soared from 256,000 in 1871 to 490,000 in 1880, swamping the Maori population of less than 50,000. The Selwood family, James, Helena and young Henry, were one of the beneficiaries under the Vogel Assisted Immigration Scheme, and, with their subsequently large family, undoubtedly helped to boost the population.

Vogel made a bold promise to build 1,000 miles (1,600 km) of railway lines by 1880 and he achieved this. New Zealand’s rail network increased from just 74 km in 1870 to 2000 km in 1880. The rail and road infrastructure boost in the 1870s radically transformed much of the natural environment, facilitating the opening up of new lands for pastoral faming through forest clearance, flax-milling and swamp drainage.

Telecommunications were also taking a hold in the latter half of the 19th century. The telegraph, connections using Morse code through a copper cable, was introduced in the 1860s, and Invercargill was connected to Dunedin and Christchurch by 1865. Graham Bell introduced the telephone to the world in 1876, and within 10 years there was a nationwide telephone network, reaching Invercargill. Post and telegraph offices were established nationwide and by 1880 there were 850 post offices. Private telephone connections through a local telephone exchange took much longer to establish. The end of the 19th century led to a few decades where coal was king and the rail was the principal means of transport. It was after the end of the 19th century before we had the beginning of hydro power stations, a reticulated national power grid, petrol and diesel powered cars, trucks, tractors, air transport, plastic, radio, and television.